Magnetism occurs when electrons in certain magnetic materials move in a certain way. As these electrons rotate, they form a pair of unique poles, one “S” pole and one “N” pole, like two sides of the same coin. When two magnets with the same polarity (North-North or South-South) are placed together, they repel each other (like poles repel each other). But the North and South poles will be combined (opposites attract each other). In our modern life, magnets have been widely used in motors, headphones, speakers, toys, machines and other devices.

However, how are these magnets made? Today you are fortunate to be here, follow me to understand the science and process technology behind the conversion of ordinary mineral materials into magnetic entities, such as batching, smelting ingots, powder making, magnetization, pressing, sintering & bonding, grinding, pin cutting, surface treatment, etc. Familiarity with these manufacturing processes can not only deepen our confidence in the future of magnetic products as practitioners in the magnetic industry, but also let us understand how they are so imaginatively constructed.

How are Magnets Made?

Making magnets is simply the transformation of raw materials into something that has a particular magnetic signature. They are achieved by having optimum control over material selection, processes and machinery at every step of production. Each magnet, whether permanent, soft or rare-earth, requires a different design and material depending on its purpose and performance. The following is an outline of the key steps of magnet production:

- Material Selection

- Smelting

- Powder Metallurgy

- Magnetization

- Forming and Shaping

- Sintering

- Annealing

- Bonding (Optional)

- Grinding

- Cutting

- Surface Treatment

- Magnetic Calibration

- Finished Product

All the steps need not be performed for every magnet production, and may be not sequentially done. Sintering and bonding, for instance, are two crucial ways to shape and size magnets, but only one of them is applied depending on the magnet being made. Some magnets use sintering for structural rigidity and uniformity, and others bonding for its versatility and affordability.

Some processes like magnetic alignment are essential for building highly complex magnetic assemblies & components, but can be skipped for simple magnet pieces like disc magnets or magnetic bars. These differences emphasize the necessity of a modular manufacturing process that adapts to the specific needs of each magnet. Consider the details of each step in this complex manufacturing process of permanent magnet to find out how magnets are developed to meet multiple industrial and technological requirements.

Material Selection

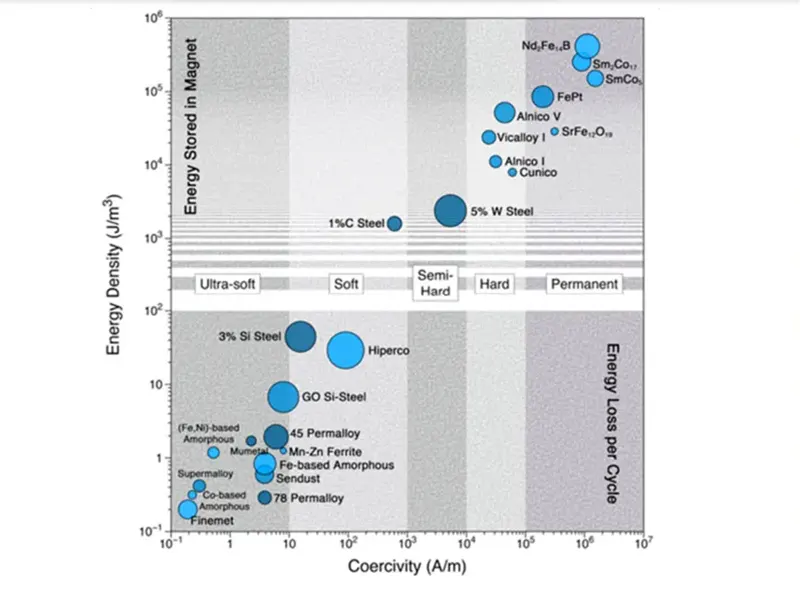

The first step in producing magnets is selecting the raw materials. The material used can vary tremendously depending on what kind of magnet you are making, and that choice affects the physical behavior of the magnet. The elements of choice for the permanent magnet manufacturing process are typically iron, cobalt, nickel and rare earth element like neodymium, samarium or dysprosium.

All alloys are selected because the composition of an alloy affects properties like coercivity (demagnetisation resistance), magnetic strength, thermal stability, etc. The different kinds of magnets, soft magnets (requiring a current to generate fields) and hard magnets (retaining their magnetisation), use different combinations of material to bring those characteristics into equilibrium.

For Example:

- Ndfeb magnet manufacturing process include mostly neodymium, iron and boron. They are common in the high performance realm.

- Samarium-cobalt (SmCo) magnets, a combination of samarium and cobalt, are highly prized for their high temperatures and corrosion resistance, though they lack the reactivity of neodymium magnets.

- The aluminium, nickel and cobalt alloy-based Alnico magnets have excellent temperature stability and are ideal for applications involving very high temperatures.

- The most economical magnets, which are primarily composed of iron oxide with barium or strontium, have less magnetic strength than rare-earth magnets.

Every material has its merits, some chosen for their high-temperature tolerance, some for their strength, and some for their affordability. The application affects the choice of materials and influences the performance and stability of the final magnet.

Smelting

Upon selecting the raw material, the next stage in magnet production is smelting. This is where the selected ores, typically iron, cobalt, nickel, or rare-earth metals such as neodymium, samarium or dysprosium, are elevated to near-sterile temperatures in a furnace. The process of smelting involves converting the raw ores into an alloy.

It involves fine-tuning the furnace’s temperature and air conditions for this process. The molten metal should be kept at the perfect temperature so that no undesirable chemicals are added and the metals combine. The composition of the alloy is regulated at this stage, because the percentages of elements such as iron, nickel and rare-earth metals all have profound effects on the properties of the magnet, including its coercivity, magnetic strength and resistance to temperature. This alignment is important because it controls the magnet’s magnetic power and uniformity.

In hard magnetic alloys such as NdFeB or SmCo, magnetisation defines the enduring magnetic nature of the finished product. In this process, individual particles of the material are temporarily dragged into the direction of the magnetic field and brought into homogeneous alignment. The technique ensures that, after the completion of the moulding process, the magnet will have a high-accuracy, isotropic magnetic field, which is of crucial importance for all applications where accuracy and reliability are necessary, e.g., motors, sensors and other magnet devices.

This is an important step in sintering magnet production, as the position of magnetic domains defines the magnetic strength and stability. In a few cases the material may be magnetized more than once, each time with a different magnetic field strength to reorient and then enhance the magnet’s performance.

Powder Metallurgy

After the solidification of the smelted alloy into ingots, the next most important stage is powder metallurgy, namely the powderation of the alloy to a powder fine enough (e.g. bombarded with neutrons) that single crystals or even nanocrystals can be chosen and grown from it. Powder metallurgy is essential for producing both sintered magnets and bonded magnet manufacturing process, which are the most common types of magnets used in various applications. The procedure starts with grinding or pulverizing the alloy into a very fine and homogeneous powder. The diameter of the powder particles has an important role to play in finalising the magnetic properties of the magnet. Uniform particle size provides uniformity, which is critical to obtaining reproducible magnetic behaviour in reality, i.e., across all produced magnets. This precision is realised, however, by the use of special equipment, like ball mills, jet mills or vibrating mills. Such machines are made to roll the material to the required fineness, and at the same time to keep the particle uniformity. Heavy balls are used in ball mills to break down the material, and high-pressure air, in jet mills, generates severe friction to break down the material to finer particles. It is used to grind material down to a powder by a high-frequency vibration mechanism. In recent years, a new technology has become popular in the manufacturing process of neodymium magnets to replace traditional powder metallurgy, which is “Hydrogen decrepitation. This method can make the particle fineness even smaller.

The powder is subsequently mixed with other materials according to the desired formulation of the magnet. For example, additives or binders can be added to improve the mechanical contact between the particles or to improve the final material characteristics. It is desired to prepare a uniform mixture which can be easily pressed into a desired magnetic shape, for example, a shaped magnet. This step is crucial in order to guarantee the homogeneity of the final magnet, since any uncertainty on the particle size, mixing, or binder composition that may be present in the mould can result in inhomogeneity of the magnet strength, shape and size and behaviour. Once the powder is adequately prepared, it is ready for the next stage in the magnet production process, where it will be shaped into the desired form before undergoing further processing.

Magnetization

Before the magnet is moulded, the raw material can be subjected to a magnetization process. Magnetization is commonly induced by bringing the material under the action of a strong external magnetic field, usually provided by powerful electromagnets or dedicated magnetizing machines. If the powder or material is exposed to this magnetic field, then the single magnetic domains (regions in the material where the magnetic moments of atoms align in the same direction) align themselves with the field. In this sense, this alignment is critical, as it decides the intensity and homogeneity of the magnet’s magnetic characteristics.

In materials such as hard magnetic alloys i.e., NdFeB magnet manufacturing process or SmCo manufacturing, magnetization is the base to build the ultimate permanent magnetic properties. In doing so, the magnetization of the individual particles of the material is localised for a certain period of time in the direction of the external magnetic field, giving the material a uniform magnetisation. The process ensures that when the magnet is fully shaped, it will have a strong and uniform magnetic field, which is critical for applications requiring high precision and reliability, such as motors, sensors, and other magnetic devices.

Especially in the production of sintered magnets, this step is of greatest interest because the orientation of the magnetic domains is the key to obtaining the required magnetic strength and stability. In certain instances, the material can experience a sequence of magnetization cycles with the strength of a magnetic field that is varied from cycle to cycle in order to maximally align the magnetization and thus, improve the performance of the magnet.

Pressing (Shaping)

| Pressing Technique | Description | Advantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cold Pressing | The powdered material is pressed at room temperature using high-pressure presses. | High density and uniformity, Maintains dimensional accuracy | Sintered magnets, Magnets requiring high-density |

| Hot Pressing | Material is heated before pressing, allowing for higher-density magnets with improved mechanical properties. | Higher density, Reduced porosity, Improved mechanical strength | Complex shapes and magnets requiring enhanced properties |

| Isostatic Pressing | Uniform high pressure was applied from all directions to compact the material evenly. | Uniform density, Reduced porosity, Ability to form complex shapes | High-precision sensors, Complex-shaped magnets, Miniature magnets |

Sintering

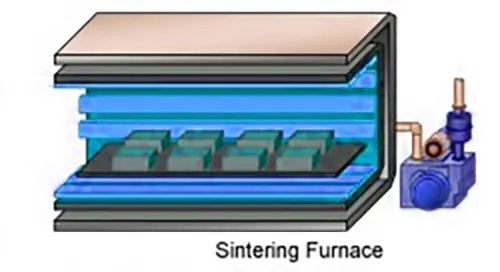

After pressing, one of the most important steps in the production of magnets is sintering. It involves heating the melted stuff in a furnace at many degrees below the melting point, generally around 80-90 per cent of the melting point. As powders bind to one another and fuse into a solid mass, they sinter. As well as tying the particles together, sintering brings the magnetic fields of the material in sync with each other, which is essential for achieving the magnetic properties you desire.

Temperature, time and atmosphere all influence the final magnet shape. Temperature should be kept low enough that the material isn’t hot enough to lose its magnetic power or crack. Also, The sintering time also influences the density and strength of the final magnet; longer sintering times produce denser and more robust magnets. The second is the furnace atmosphere: a vacuum or inert gas or hydrogen-enriched atmosphere in a controlled state prevents oxidation or contamination that might undermine the performance of the magnet.

Annealing

Annealing (or tempering) is a procedure of heating up the magnet after sintering in order to make it stronger. The process involves slowly heating the magnet to a set point and then cooling it off. In this gradual cooling, the material stretches away stresses that might have developed during sintering, making it less fragile and more mechanically robust. Annealing also smoothes the microstructure of the material, improving its mechanical and magnetic properties.

This heat treatment is critical for stress control since it helps eliminate stresses in the interior which could cause cracks or other deformations that weaken the magnet and make it stronger. Moreover, annealing hardens the material by increasing its microstructure, and thus its mechanical properties. The procedure can also tune the orientation of magnetic zones in the material to generate a stronger, more stable magnet. Additionally, annealing reduces defects (such as cracks or holes) that might have been formed by sintering. After annealing, the magnet becomes more stable and resistive, stronger magnetically and mechanically, and can reach its final stage of machining and processing.

Bonding

Bonding is also used in some cases if the magnets have some complicated shape or are weak enough to not be magnetically powerful. Bonded magnet manufacturing process involves mingling magnetic powders with a binder (usually plastic or resin) to create a paste. The solution is then injection or compression molded into the desired form. Once formed, the material is dried so that the binder solidifies and the magnet sets. Bonded magnets are especially good for thin, delicate parts where sintered magnets might be too weak or inaccessible to manufacture. They are also less likely to crack, and are thus best suited for those applications that require flexibility or strength in small, intricate designs. In addition, bonded magnets are easier and cheaper to produce than sintered magnets, and are suitable for mass-producing motors, sensors, toys and other small electronic devices. It is also easier if it needs multiple shapes and sizes to add more fluidity to the design.

Grinding

Once sintered or bonded, the magnets are ground down to the proper size and flatness. The magnet is then ground to precise tolerances and finished by high-precision grinding machines. This is an essential step if the magnet is intended to fit into a fixture or a system that requires exact measurements. The grinding also removes any bumps, burrs or flaws of the previous fabrication, so the final product is perfectly imperfect. This is done to create a flat, accurate, well-balanced magnet that will perform well in high-power devices, such as small motors, sensors or electronics. Grinding can be performed to extremely fine tolerances in high-precision applications to ensure the quality and durability of the magnet in end use.

Cutting

Cutting is the last step of magnet manufacturing process, where a magnet must be cut up or bent into specific shapes. Cutting methods vary based on the hardness of the material and the level of accuracy required. Some standard techniques include laser cutting, waterjet cutting and diamond cutting, which all provide high precision and smooth surfaces. Such cutting comes in handy when fabricating magnets that must be inserted in certain locations or changed for special uses. This is especially important when making complex magnets for complex machines – such as electric motors, magnetic sensors or medical instruments – where the magnets need to fit snugly into their narrow design space. If you want absolute accuracy, laser cutting and waterjet cutting are your go-to because they cut the most intricate shapes without blowing up the material or making it scorch. Once the magnets are cut to size and shape, they can be connected to their product or device.

Surface Treatment

This last step is surface treatment, where protective corrosion resistant coatings are applied to the magnet surface to prevent corrosion and damage. Depending on the purpose and the type of magnet, it’s important to choose the right coating. Common surface treatments include:

- Electroplating: Applying a thin coating of metal, like nickel or zinc to keep the magnet from rust and corrosion. Electroplating also improves the aesthetic of the magnet.

- Spraying (Powder Coating or Painting): In some instances, magnets are spray-coated to make them durable, especially in harsh environments.

- Epoxy coating: Epoxy resin can be applied to provide further corrosion protection, for example, neodymium magnets used outdoors or underwater.

The type of coating depends on the magnet’s operational conditions and factors such as temperature, moisture and chemical resistance.

Magnetic Calibration

Magnetic calibration is the process of making and treating the magnet to verify that its magnetic behaviour meets the specifications. When calibrated, the magnet’s field strength, polarity and orientation are carefully monitored and corrected. This process makes sure all of the magnets in a batch perform reliably and consistently. Calibration is particularly important in extremely accurate situations like motors, sensors or magnetic bearings where constant magnetic force is essential.

Finished Product

Once smelting, powdering, pressing, sintering, bonding, surface treatment and magnetic calibration is complete the magnet is packaged and shipped. The final magnets are checked for their magnetic quality, dimensional correctness, and surface quality. This resulting device can now be incorporated into all sorts of devices from tiny electronic devices to large industrial equipment, in which they serve a diverse set of purposes.

Get Osencmag's Custom Magnets & Magnetic Assemblies products.

We specialize in providing custom magnetic solutions, taking every step of the manufacturing process with a serious attitude. Whether you need a custom permanent magnet shape, a special magnetic accessory, or a complex magnetic assembly, our team knows that every stage can be handled with care and accuracy.

From selecting the right raw materials such as iron, nickel, or cobalt to using state-of-the-art magnetization technology, we maintain tight control over all stages of production. Having Osencmag as your magnet manufacturer means that every magnet you get is made precisely to your specifications. Our professionals spend a great deal of time with you to find out what you are looking for and use our 20+ years of accumulated knowledge to find the best solution.

FAQs

What are the methods of making a magnet?

Although powder metallurgy is the standard technique, there are several other techniques for forming magnets. Single-touch involves subjecting ferromagnetic metals such as iron and nickel to a strong magnetic field, which sets the materials’ internal regions in an identical alignment, yielding a permanent magnet. The double-touch approach employs two magnetic fields, one to magnetise the material and another to increase magnetic coherence. You can also pass a wire attached to a ferromagnetic core through which an electric current passes to create a strong magnetic field and an electromagnet.

What is the manufacturing process of ferrite magnets?

The manufacturing process for ferrite magnets involves mixing ceramic materials, iron oxide (rust) and barium, strontium, or a selected carbonate material, and then grinding and pressing them together in a press to form the desired magnet shape. After forming, the material undergoes a sintering process at high temperatures (usually around 1200°C or 2192°F). Specific shapes also require a bonding process.

What are the raw materials used to make magnets?

The raw materials used to make magnets can vary, depending on the type of magnet you want to make and the performance requirements. Permanent magnets are made from alloys that typically contain different proportions of iron, aluminum, nickel, cobalt, and the rare earth elements samarium, dysprosium, and neodymium.

Iron, cobalt, and nickel are the most common base metals used in the manufacturing of permanent magnets (such as those found in motors, sensors, and electronics). These metals are converted into other forms of magnets. For example, the AlNiCo magnet manufacturing process involves the use of aluminum, nickel, and cobalt. Ferrite magnets are made from iron oxide with barium or strontium. The strongest magnets are neodymium iron boron (NdFeB) magnets, which are made from a mixture of neodymium, iron, and boron. In addition, samarium cobalt (SmCo) magnets, which contain samarium and cobalt, have superior heat resistance.

What creates a magnet?

Electrons spinning around the nucleus of an atom create tiny magnetic fields. The molecules of materials in a magnet (iron, neodymium, nickel, and cobalt) are arranged in such a way that their electrons spin in the same direction, creating north and south poles. The alignment of these electron spins is key to the strength and polarity of a magnet, which is why magnets are usually made from materials that are ferromagnetic (materials whose electron spins tend to line up easily).

How are magnets made permanent?

Permanent magnets are made by aligning the internal structure of ferromagnetic materials in a strong magnetic field during the manufacturing process. This process makes it difficult to demagnetize the magnet. They are usually made from “hard” ferromagnetic materials such as alnico and ferrite that are subjected to special processing in a strong magnetic field during manufacture to align their internal microcrystalline structure, making them very hard to demagnetize.